Small (but Mighty!)

Fungi are so variable – from single-celled yeasts to the biggest living organism on earth (Armillaria ostoyae covers nearly 4 square miles in an Oregon forest…and is a butt rot!). Others are small but mighty, like the artillery fungus.

Also known as the shotput fungus or the cannonball fungus, the artillery fungus is most often found in mulch. Its Latin name, Sphaerobolus stellatus, means star-shaped sphere thrower. Other species of Sphaerobolus have been identified as well, including S. iowensis (Iowa-shaped sphere thrower? Sphere thrower from Iowa?). The name alone implies that this fungus has a colorful story to tell.

They resemble little, teeny tiny cups that grow in landscape mulch, about 1/8” in size. Their ‘cup’ holds a mass of sticky spores called a gleba. Water pressure builds up in the ‘cup’ and eventually blasts the gleba out into the world. Being sticky, the gleba sticks to the surface where it lands and looks like a small, shiny black speck.

What’s so mighty about that?

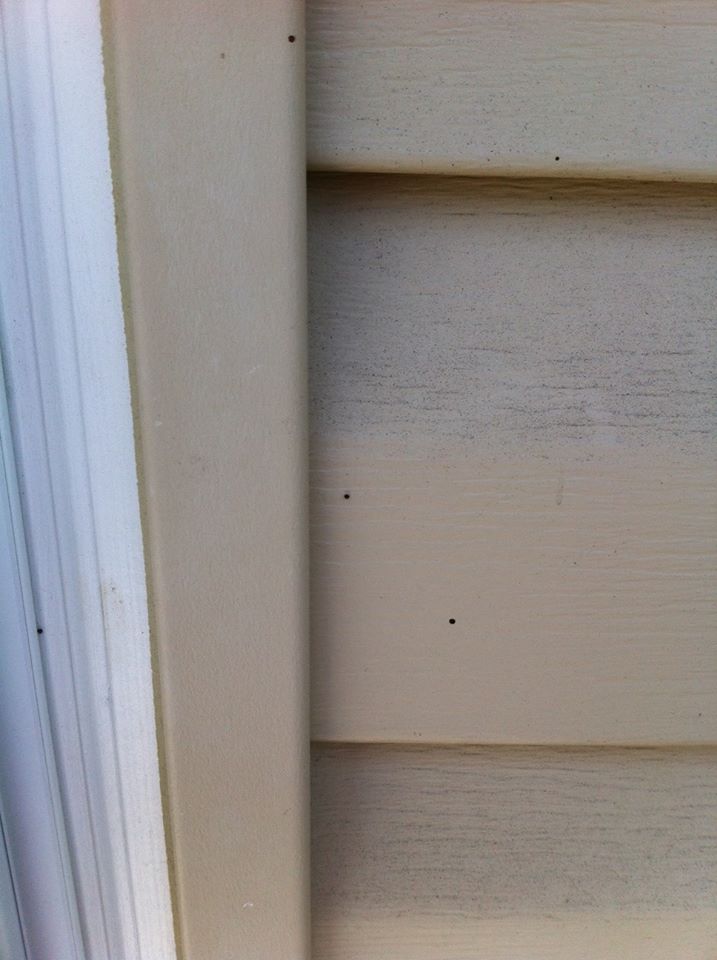

Well, researchers documented a gleba shot as far as 18’ in length and 14’ in height. For perspective, that is equivalent to a six-foot-tall person throwing a baseball almost two miles away and nearly 1.5 miles high. Since this fungus is prevalent in landscape mulch, homeowners with light-colored siding often report headaches from trying to scrub scads of tiny black spots off their home or car. If the siding is wood, spores could germinate and slowly degrade it, if enough moisture is present. In addition to being super sticky, the glebal mass is quite resilient, and its job is to protect the spores within it. Research has shown that even when the gleba is kept dry and dormant for 11 years, spores are able to successfully germinate once exposed to ideal conditions (moisture is key).

This is another example of a wood decay fungus. Artillery fungi prefer mulch as a food source, since it is usually moist. The type of mulch doesn’t seem to matter. Researchers at Penn State have tested 27 different kinds of mulch, and all supported Sphaerobolus spp. growth eventually. However, they do seem to favor the north side of houses, which tend to have cooler temperatures and shade.

North side of a house featuring Sphaerobolus stellatus

The dark side

New plant diseases don’t come along that often; so, it’s a fairly big deal when it happens. One of the newest turf diseases is attributed to (you guessed it!) the artillery fungus. Turns out mulch isn’t the only substrate they consume.

Back in 2010, a handful of golf courses in New Zealand, Scotland, and the US reported small dark rings that resembled fairy ring, except that the turf was sunken within the ring. It looked as though the ring had collapsed; thus, the name ‘thatch collapse’ was coined. In all cases, the golf course had high levels of organic matter.

Dr. John Kaminski and his lab, at Penn State, led the charge to identify the culprit, and they pinpointed S. stellatus as the offender behind this new disease. Thatch collapse is most noticeable on putting greens, since they are maintained at such a low height. Researchers theorize that thatch collapse could occur on home lawns but would be less noticeable.

Dr. Jill Calabro

HRI Science & Research Director

Share This Post