The Furtive Foe of the Forests

For most people, mistletoe conjures warm feelings of holiday traditions.

Not me. You won’t find mistletoe in my house.

Sure, the sprigs of leafy, evergreen mistletoe you strategically hang in your doorway as an excuse to kiss your sweetie during the holidays may be lovely, but it just reminds me of its grave cousin, dwarf mistletoe.

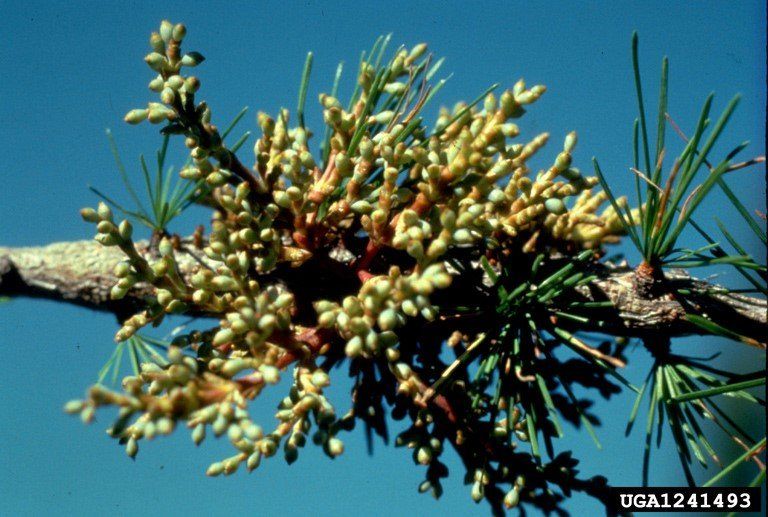

Dwarf mistletoe infections cause spindle-shaped swellings on branches and small stems. Dwarf mistletoe shoots begin to sprout in the spring eventually forming clusters of shoots as seen in this plant. Photo Credit: USDA Forest Service, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Dwarf mistletoe is the plant parasite responsible for severe damage to conifer forests, especially in the Western U.S. The U.S Forest Service estimates at least 43% of all Douglas fir stands in eastern Washington are infected with dwarf mistletoe. And you may never see this fearful assassin, despite it operating in plain sight.

It starts as a seemingly harmless thief.

Dwarf mistletoe begins it sordid journey from a seed (it is a plant, after all) that germinates and taps into the tree host vascular system to burgle water and nutrients. From there, it is slow to develop. In fact, it can take one to two years to notice any change to the tree, and even then, it’s usually subtle. The first signs of any harmful activity appear merely as some swelling or distortion of the infected branch. Another two to three years later, the mistletoe plant itself emerges as leafless, olive green-colored, small shoots on infected branches that easily blend into conifer needles. Two years after that, seeds are produced, for a grand total of about six years to complete its life cycle. Even more wicked, this furtive foe can lie dormant in a tree for years in dense stands until light levels are adequate.

They have their own superpower. Their sticky seeds are forcibly ejected at speeds clocked around 60 mph and can land as far as 30-40’ away. Most only go about 10-15’ though. That’s when the cycle starts all over again.

So how do we know it’s there?

One clear symptom that dwarf mistletoe is mischief-making, is when the tree starts producing witches’ brooms. As the mistletoe colonizes the tree, interior buds are eventually pillaged. This invasion stimulates the buds to produce a dense mass of shoots (instead of just one under normal circumstances) that resembles a bird or squirrel nest. That is a witches’ broom.

The poor, unsuspecting, victimized tree suffers a slow decline, as nutrients and water are stolen. Growth rate is slowed, the tree shape becomes grotesque, and branches are more prone to breakage. First the top of the tree declines, as lower, infected branches demand more and more resources. Meanwhile, the mistletoe spreads within the tree first by moving upward about 4-6” each year and outward to adjacent and lower storied trees. As a tree is compromised, insects, wood decay, and climatic factors often finish the tree off. Full-on mercenary action.

Just to be clear, the common leafy mistletoe is a plant parasite as well, just not as effective. It can absolutely damage trees (especially deciduous trees) and result in their decline, but it is not considered as ruthless as dwarf mistletoes.

Mistletoe management is a major challenge and relies on pruning, removal of infected trees, and planting nonhosts. Removing mistletoe shoots (if you’re lucky enough to see it) is insufficient; often it will just regrow there the next year.

Dr. Jill Calabro

Research & Science Directo

rHorticultural Research Institut

All photos courtesy J. Calabro, unless otherwise noted.

Share This Post