Too Much of a Good Thing: the Story of Mulch Volcanoes

Welcome, Spring! Tender, new leaves are emerging, blossoms are blooming, plants are waking, and a fresh new crop of mulch volcanoes has formed. It’s almost as if they appear overnight – one day everything is peaceful and quiet in the landscape; the next day mulch volcanoes are everywhere. And they are not good.

They look innocuous enough, just simple mounds of mulch around a tree. But underneath lurks a hot bed of trouble waiting to slowly erupt. They form under good intentions, often to help protect trees from lawn mowers and weed whackers. When the mulch is too thick, those well-meaning deeds lead to more stress for the tree.

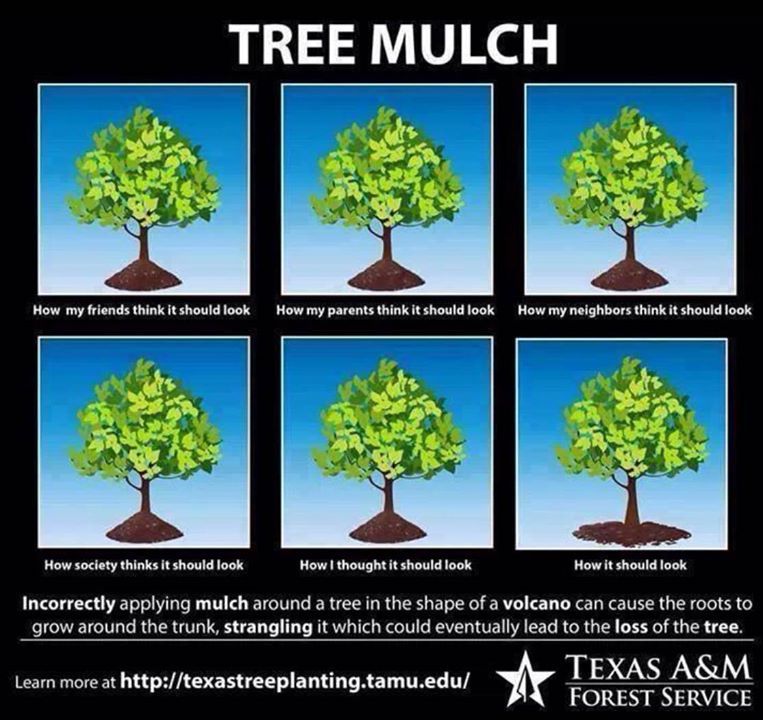

Ideally, mulch should be no more than 2-3” thick, spread about 4-6’ diameter around the trunk, and not touch the trunk. This amount benefits trees greatly by acting like a blanket by moderating soil temperatures to keep summer temperatures down and winter temperatures up. Soil structure improves as well – aeration is better, erosion is lessened, and water can better penetrate the soil surface. Surface evaporation is also reduced, helping maintain soil moisture.

Source: Steve Bullmanl, arbtalk.co.uk

Mulch reaches volcano status when it reaches a depth of around 8-12”, sometimes more! This creates an environment where there is not enough oxygen for roots. The mulch compacts over time, which makes it even harder for roots to have access to oxygen. And it can smell bad. Fresh mulch should smell earthy; bad mulch turns sour from the buildup of hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg smell). Plus high mulch layers cause tree bark to rot and crack. This leaves the tree more susceptible to rodent damage, bark decay, and tree diseases (remember butt rot? Long live butt rot!).

Often the tree can confuse the mulch for soil and send out secondary roots all throughout the mulch. These shallow roots can encircle the tree or even grow upward instead of spreading outward, creating a weak support system for the tree. Shallow roots are also more susceptible to drought stress than those in soil.

All that translates to a slow death for the tree.

This can be corrected with a little hard work. First the mulch must be removed down to the soil line. Care must be given to remove secondary roots found during excavation, especially those encircling the trunk. Then add fresh mulch but aim for more of a flat doughnut shape and avoid the lava dome look.

Here’s hoping one day we will live in a world free of mulch volcanoes!

Dr. Jill Calabro

HRI & AmericanHort Science & Research Director

Header photo courtesy J. Calabro.

Share This Post